This blog is a part of a series, you can find links to all the blogs on this page: Writing a Debugger from Scratch

In the previous two blogs we managed to learn how to stop a process, inspect its registers, memories and set breakpoint. The next major task is to add breakpoints using symbol (function) names. That is a very important feature for a debugger. If you have used GDB before, it’s what break main or break puts does.

I struggled for some decent amount of time to understand the symbol resolution, effect of Intel CET extension, etc. So in this blog I will simplify and discuss this process from a debugger’s point of view and leave out the rest of ELF details for maybe another day or put them in my notes.

Lets discuss Symbols (Functions)

Well, what is linking ? So, when we write programs, we often use libraries and call functions that do not belong to our code. For example, if we use printf() in our program, we neither declare nor define the function, we just #include the header.

Well the header, just contains the declaration and not the definition. We need a way to attach this function code (definition) to our compiled code. So this process is called linking and this is done by the linker program. In Linux its something like: /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.N (where N is a number that denotes version).

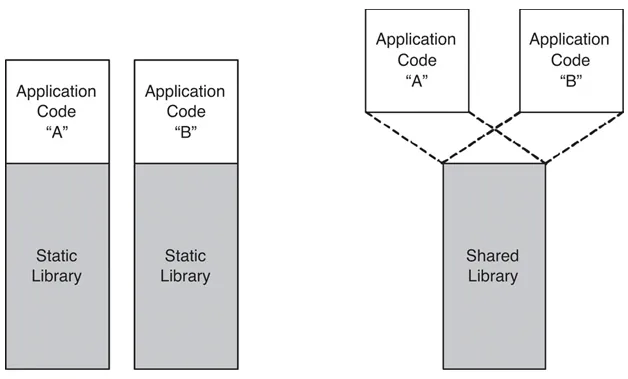

Now a large number of programs use these standard functions and since main() is also called by some other function, we need to link that too. This would result in having the same library attached to so many programs, resulting in larger binary sizes, difficulty in updating the version / library code of the library, etc. and each binary would need to ship its libraries.

These ‘disadvantages’ are debatable and now with the easy availability of storage, some people prefer static linking, it helps to avoid this version dependency hell to have the same binary run on all Linux distributions. (Distributions like arch which are ‘rolling’ distributions often have new versions of libraries in contrast to distributions like Ubuntu. So a distributor needs to manage these version changes. Backward compatibility is fine but the issue comes when the binary has to run with a newer version of library.

So to overcome these, dynamic linking was introduced. In this process, the library code is in a form called Shared Object with extension .so . The library code is shared among all the programs that require that version of the library. By shared I mean, they are just mapped(mmap) into the process’s address space.

Memory Mappings

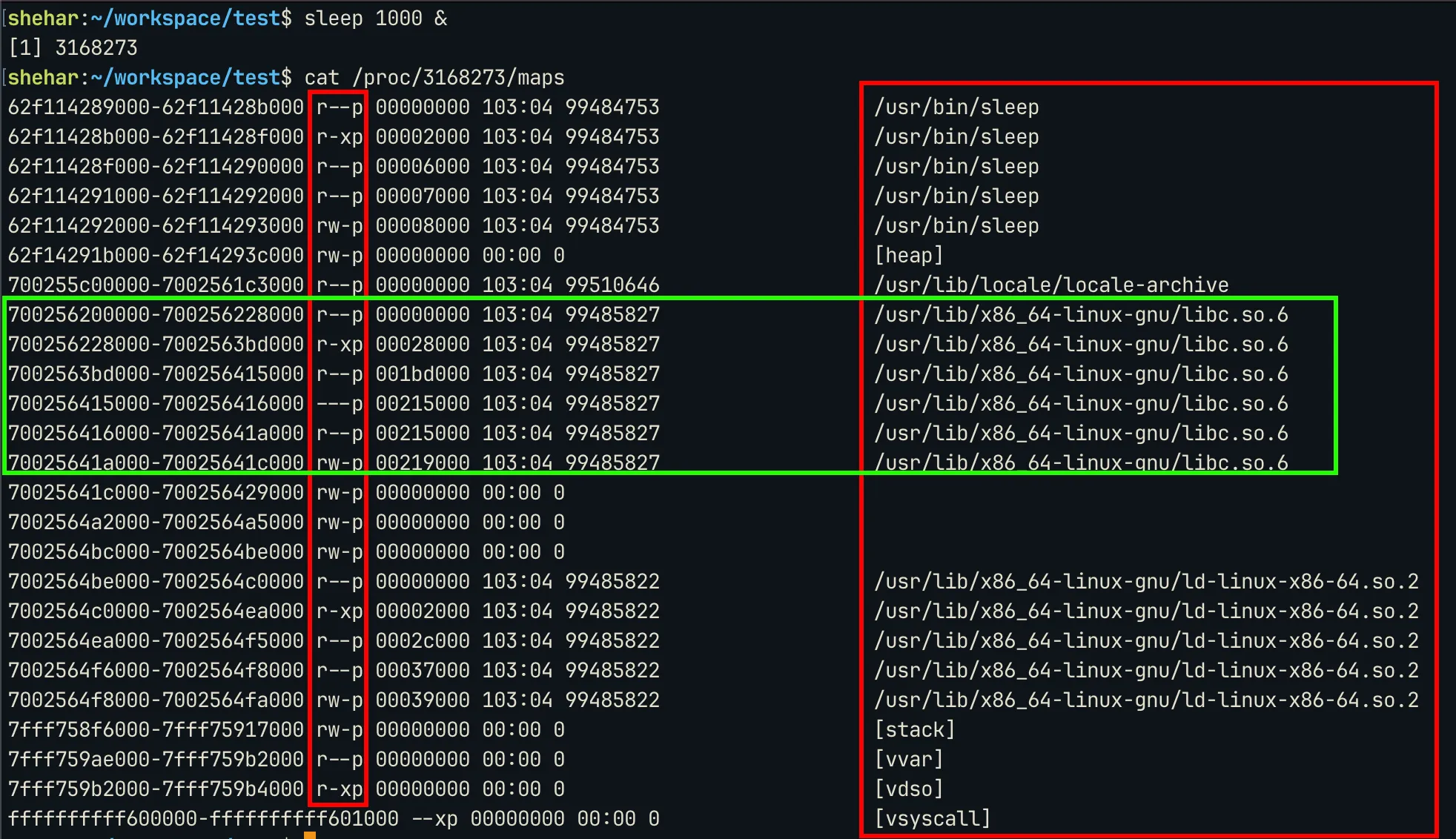

You can view the memory mappings of a process by reading /proc/$(PID)/maps file. Here is a simple example. The format for the output is:

[mem_start]-[mem_end] [perm] [offset] [dev:node] [size] [name]

The first red box denotes the permission, the maps with x bit set will have instructions. The last column denotes the names of the libraries mapped. As marked, the C library is mapped from address 0x700256200000 to 0x70025641c000 .

ELF

Let’s think about this: an application usually occupies more space than its file size (even if it doesn’t use heap memory), it also has to map the instructions in the file to the memory and many more operations are needed before the program starts to run. So how does the linker or other programs involved in the starting of the program know where to read/write memory ? So to tackle this, there is a standard way of building an object file (an executable, a .so , or a dynamic object). This standard is call the ELF (Executable and Linkable Format). Repeating the theory for ELF here would not be a good idea. So for ELF theory you can look into my notes: ELF Files.

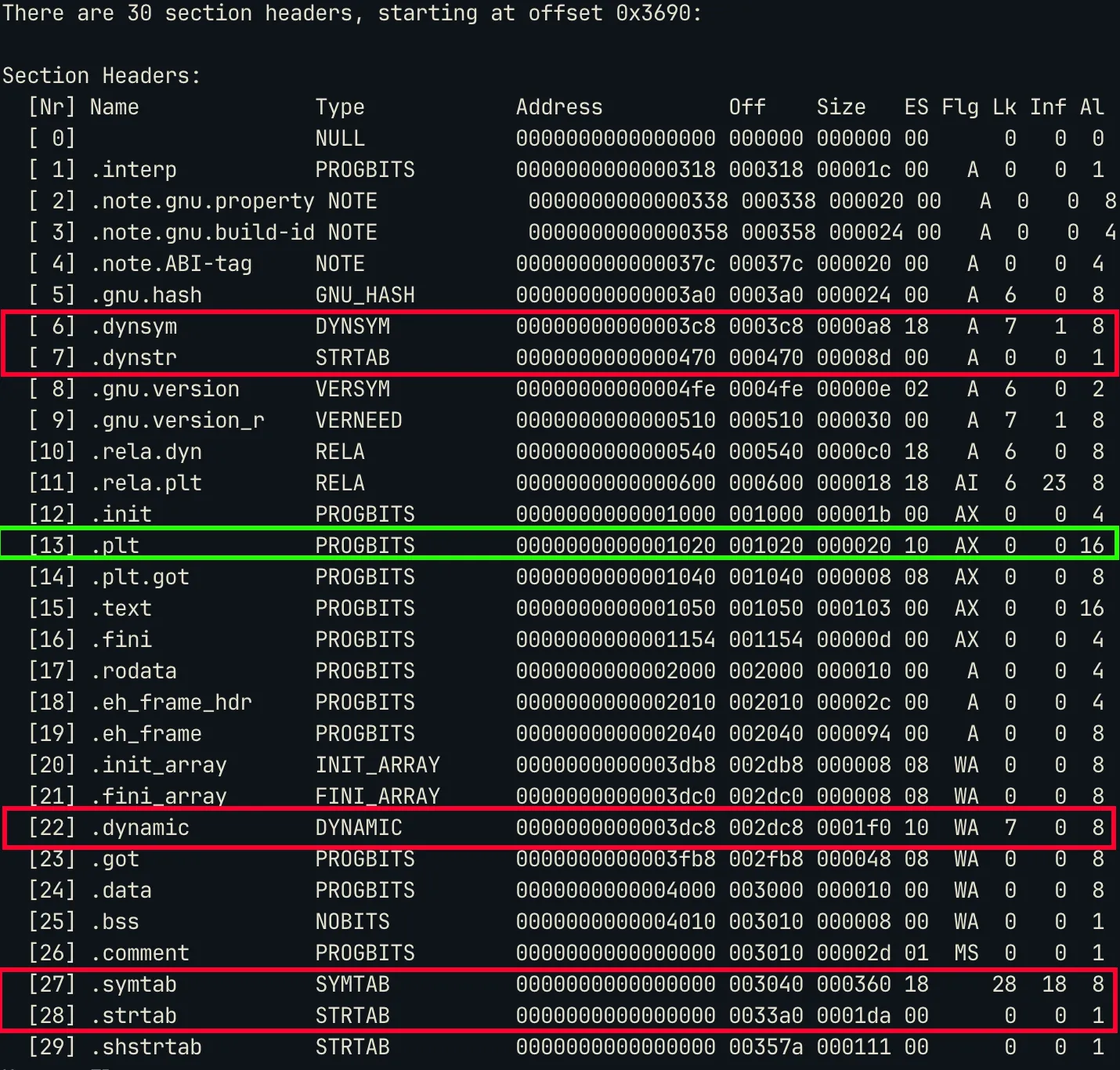

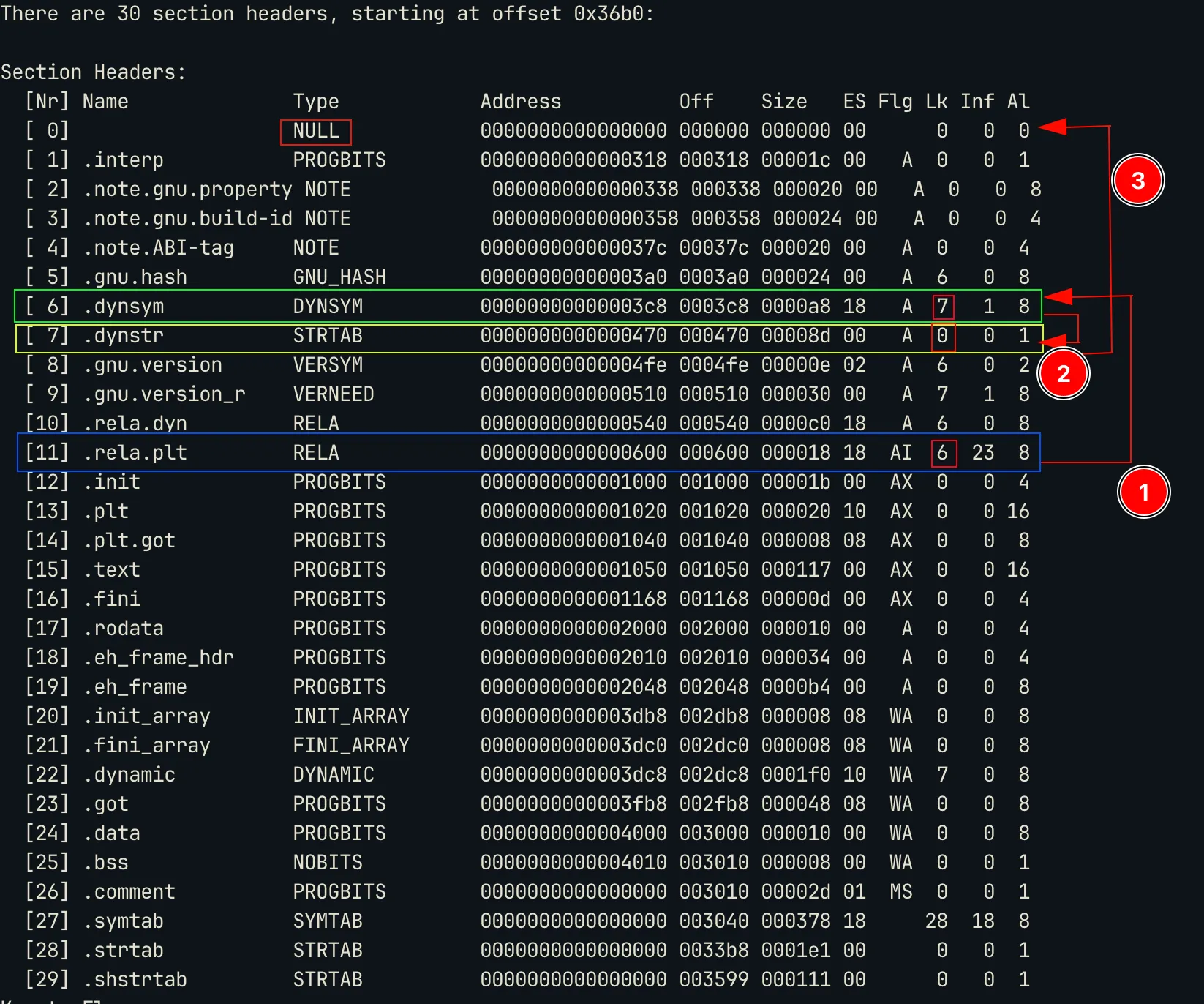

Come back to this blog after you have understood the basic structure of an ELF file, section headers and sections. Let’s move ahead with the discussion. So for the purpose of resolving symbol names to their addresses in memory at runtime we are interested in the following sections: .plt, .rela.dyn, .rela.plt, .symtab, .dynsym and .strtab.Since parsing ELF is not part of the core debugging flow, I used libelf to perform the iteration through the section headers, symbol tables, etc.

Out of these sections,

.pltis the one that has the flagsAX, hereXmeans that it’s executable. You can also notice that.symtaband.strtabhave no flags, that means they are not supposed to be mapped or copied to memory. Hence these can bestrippedfrom the binary without affecting the binary at all. This is whatstripprogram does. This makes symbol resolution very difficult especially, for static symbols (symbols for functions within the code and not library code).

Symbol Tables and String Tables

Let’s first discuss symbol tables. So if you read elf(5), you will come across symbol tables. So in the previous image, .dynsym and .symtab are symbol tables of type DYNSYM and SYMTAB respectively. These symbol tables have one entry for each symbol. If you see the Lk column in the image (stands for Link), you will see .dynsym has Lk=7 which is the index of .dynstr and .symtab has link value of .strtab .

Both .dynstr and .symtab are of type STRTAB which means they are string tables. Since each symbol has a name, the name is stored in this linked string tables. Hence for symbols in .dynsym the names are stored in .dynstr and for symbols in .symtab names are stored in .strtab.

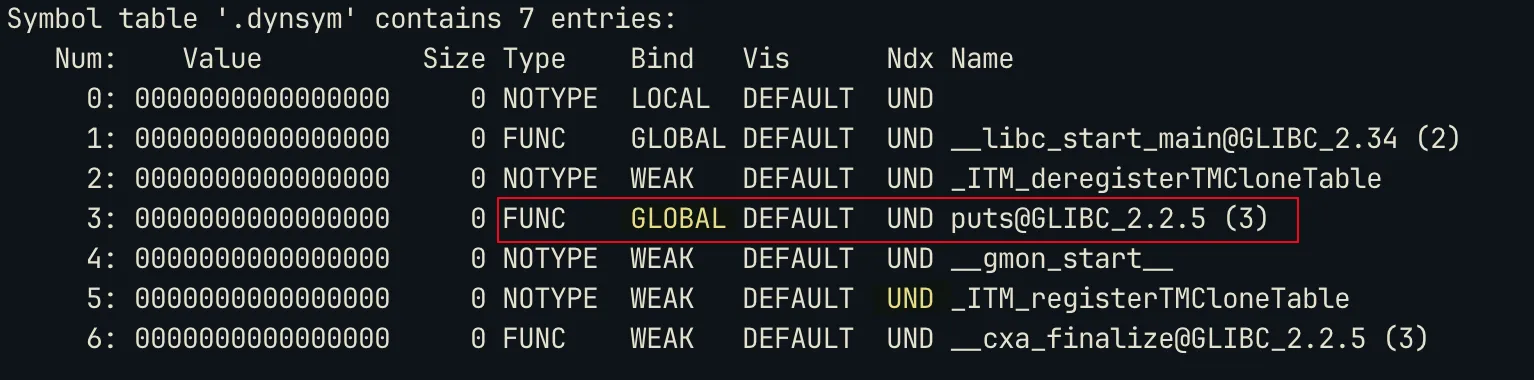

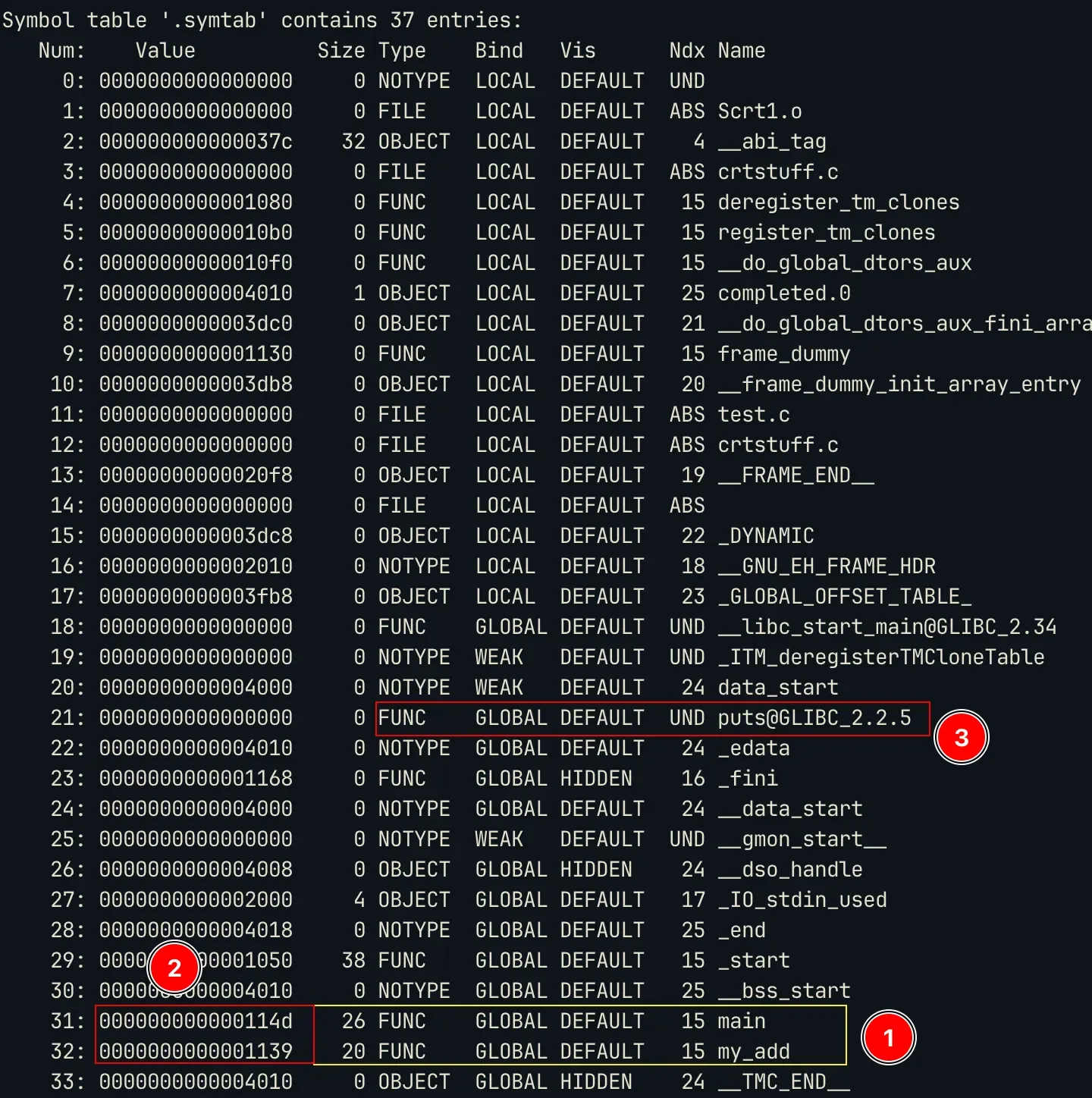

Here is a sample table entries for .dynsym and .symtab using command: readelf -sW <file>

You can notice a few things:

- The

.symtabcontains the local functions (static symbols) [1] and it also has the offset address of these functions from the base of the binary [2]. So if the base is0x55555000then the adddress of main will be0x55555000 + 0x01139=0x55556139. But if you see the.dynsymthe value it has is0x0000, this is because the offset for the placeholder of these dynamic symbols is given by other sections (.rela.pltand.rela.dyn, we discuss this later). - You must also notice that all the symbols present in

.dynsymare also present in.symtab. This means that.symtabis the superset off all symbol tables in the binary.

RELA type sections

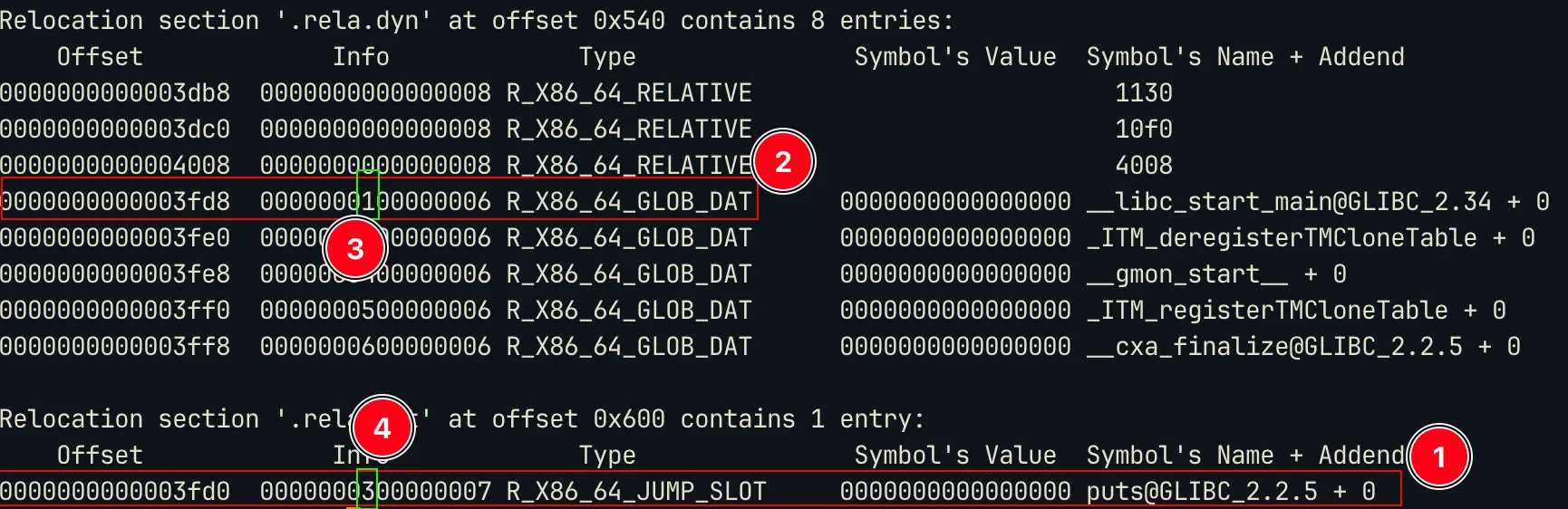

As I mentioned, the value for dynamic symbols is 0 in the symbol table. So where does the offset reside ? It resides in appropriate RELA sections. These sections contain the offset, the index of that symbol in the symbol table (dynsym) and the type of relocation.

ELF defines multiple types of relocations. I only deal with

R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOTandR_X86_64_GLOB_DAT. I will talk about these soon.

We can notice the following:

- The entry for dynamic symbols have an

offsetvalue,infoand the symbol name. This symbol name is calculated using theinfo. So the first 8 bits ofinfogive you the index of the symbol in the symbol table (.dynsym). The symbol table will then give the address of thenamein the string table (.dynstr). It’s kind of a linked list. This is how it’s done:

rela_ent = rela[i];

sym_idx = ELF64_R_TYPE(rela_ent.info) // this extracts the first 8 bits

sym_ent = dynsym[sym_idx]

name_addr = sym_ent.name // this gives the address of the name

name_str = (name_addr in dynstr)- If you see the dynsym image, you will notice that

putsis at index3and the marker 4 in the rela image also has info3. - These

offsetare usually offset of the entries in theGOTtable or Global Offset Table.

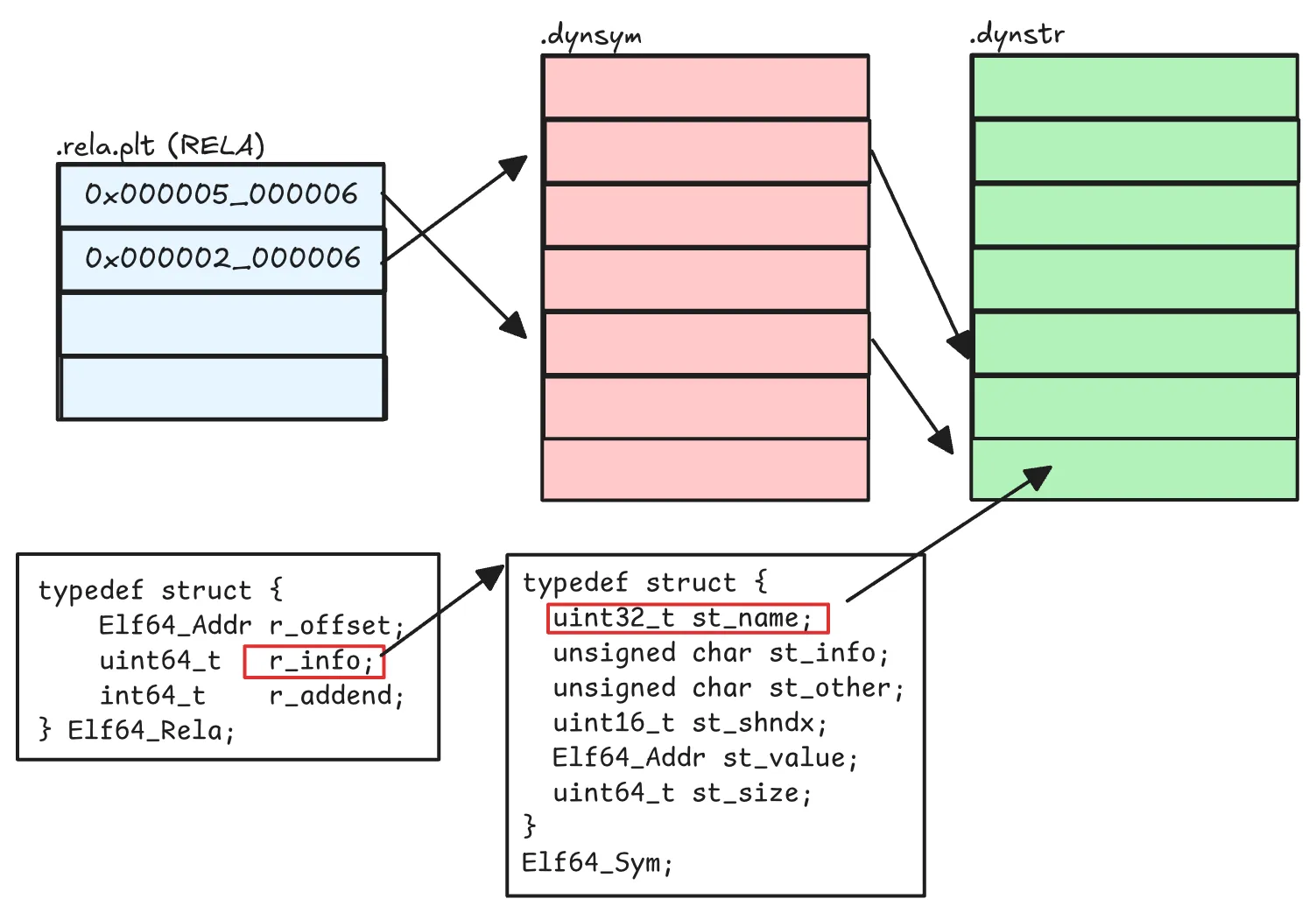

Relationship between the tables

For Dynamic Symbols:

For static symbols, RELA table is not there, so its just a simple relation between .dynsym and .dynstr. Well you may ask how do these tables know where the other is located ? The purpose of Lk or Link in the section header is to provide this.

Link[rela.plt] = index_of(.dynsym)

Link[.dynsym] = index_of(.dynstr)

Link[.dynstr] = 0 // NULL;

// So it's kind of a linked list

Relocation Types and how it happens

Lets talk about R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT and R_X86_64_GLOB_DAT.

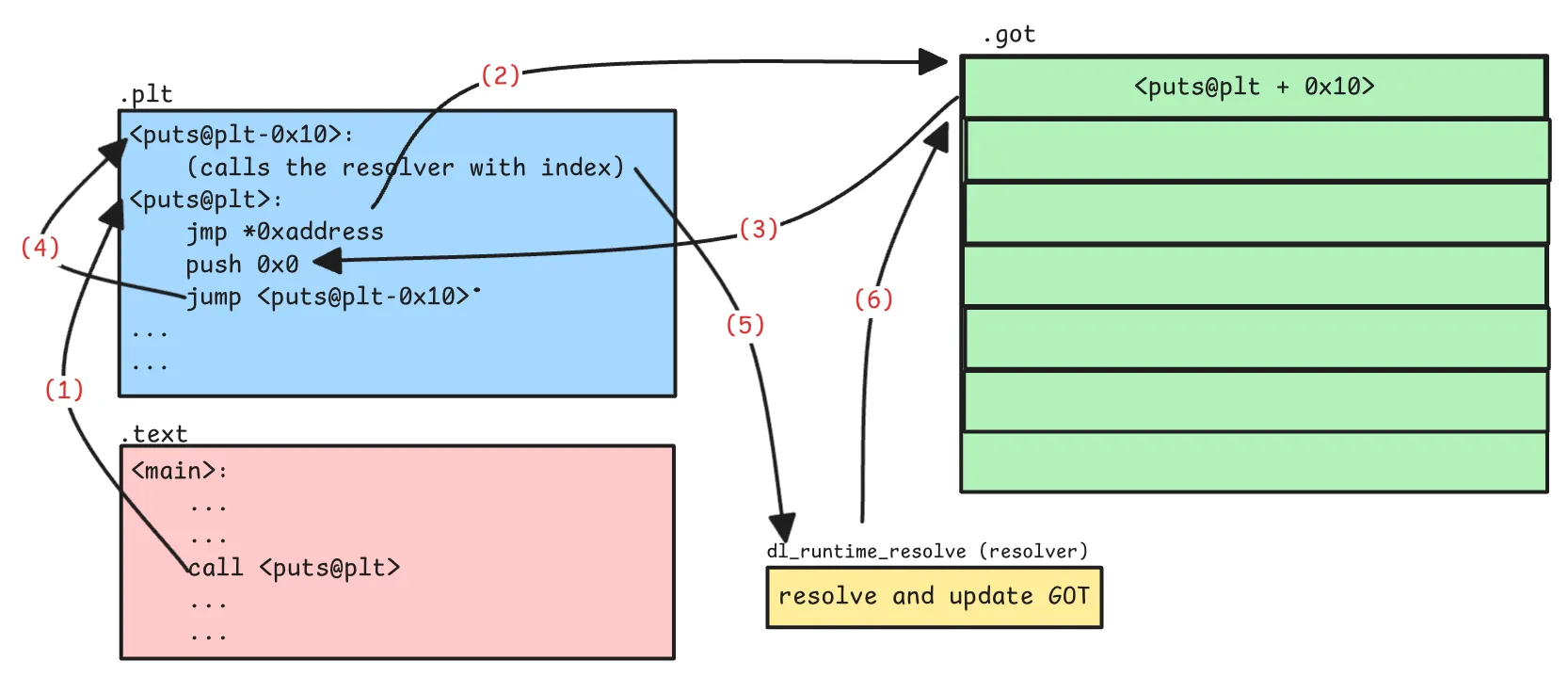

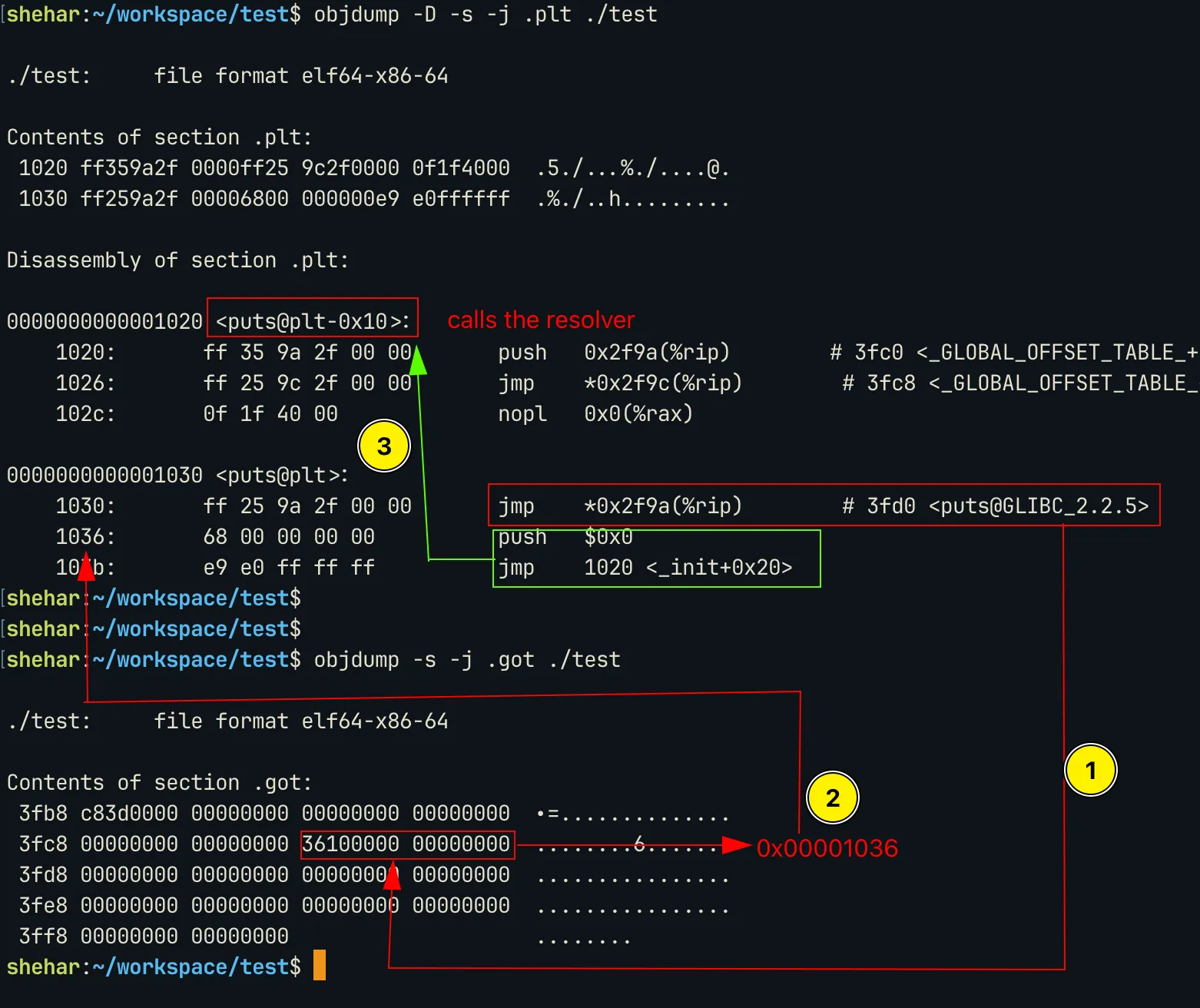

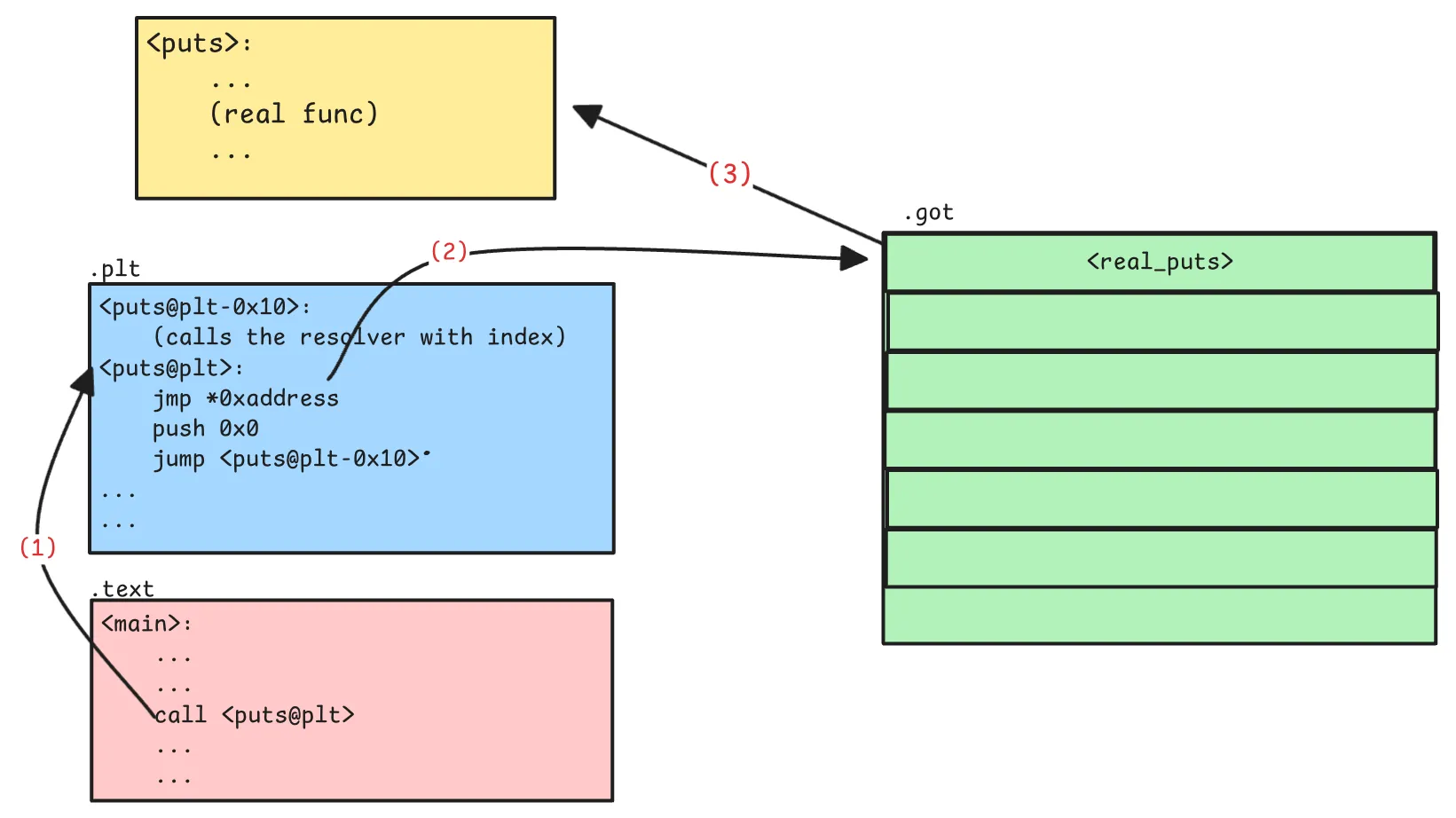

The relocation type R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT tells the linker that to resolve the address the program has to make a call to a placeholder (this address is located in the .plt section or in .plt.sec section when that is present).

Steps:

puts@pltis called. It then makes a jump to the address stored at GOT entry (the entry address is the program base + offset value as mentioned inRELAentry).- If the symbol is getting resolved for the first time, the address points back to the next instruction in the

pltentry. This then calls the resolver which resolves the address and updates the GOT.

So we will get the original address of the function only after the first call and after the resolver updates the GOT.

Next time a call is made to put@plt it make jump to the updated (real) address in GOT.

For the relocations of R_X86_64_GLOB_DAT (usually present when -fno-plt is used to avoid .plt section. The values of these in the GOT is initially 0. This is updated by the linker when the program loads the library. So how do we come to know if the value is updated or not or when the loaded loads a library.

- Do we single step every time to check the value of GOT table ? That would be very slow.

So the linker provides a way for us to know when it has started or completed adding the symbols. For this we need to go to the .dynamic section. Since this is advanced and undocumented, I would just briefly mention this.

There is a DT_DYNAMIC tag entry in the .dynamic section. This is contains an address to the struct r_debug in the tracee’s address space. This struct is a rendezvous point for the debugger and the linker. This structure has a field called r_brk which is the address to which the debugger must add a breakpoint. The linker will execute this address every time it loads an object file. Soure: glibc/elf/link.h. So if we as a debugger breakpoint this address, on hitting it, we can check the GOT values for the R_X86_64_GLOB_DAT symbols.

For R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT we still need to breakpoint the .plt / .plt.sec and then single step until GOT is updated.

.plt.secis a special case when Intel CET extensions (for security) are enabled. In this case, all the PLT entries are in.plt.secand they are executed. You can check more on this on the internet. This can be controlled by-fcf-protection=none(disables.plt.sec) or similar other values.

Summary

This was a information-heavy article. I would summarise some points to takeaway:

-

The section headers are connected in a linked list manner.

-

The dynamic symbols are present in

RELAsections. Static symbols are present in.symtab. The ELF Link Chain:.rela.plt → (via sh_link) → .dynsym → .(via sh_link) → .dynstr -

.symtabis a superset of all symbol tables. It is not present in the memory of a program, so it can be stripped without affecting the integrity of the program. -

In cases with dynamic symbols or resolution (when not build with

-staticflag),.dynamicandRELAsections must be present. -

However

.pltor.plt.seccan be removed by using the-fno-pltflag in GCC. In this case allR_X86_64_JUMP_SLOTentries are converted toR_X86_64_GLOB_DATand their address resolution follows theR_X86_64_GLOB_DATrule as discussed (usingr_debug). -

Method of resolution of

R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOTandR_X86_64_GLOB_DAT:R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT: Patch the.plt.secor.plt, then single step until GOT resolves.R_X86_64_GLOB_DAT: Breakpoint ther_brkaddress and when it hits, check the GOT entries.

Appendix

Here is a matrix of compilation flags, the effect they have:

- PLT: default

- no-PLT:

fno-plt - CET (IBT + SHSTK):

fcf-protection=full - Static:

static

| Build Flags | PLT | CET | Expected relocation | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

-fPIE -pie -fcf-protection=none | ✅ | ❌ | R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT, .plt | Patch .plt and singlestep until GOT resolves |

-fPIE -pie -fcf-protection=full | ✅ | ✅ | R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT, .plt.sec | Patch .plt.sec and singlestep until GOT resolves |

-fPIE -pie -fno-plt | ❌ | — | R_X86_64_GLOB_DAT | Breakpoint the r_brk address and check GOT when BP hit |

-static | ❌ | ❌ | No dynamic symbols; all symbols fully resolved at link time | Add the program base to the offset |